Economic growth

The exodus of Dutch nationals in the 1950s is the largest in Dutch history. Some 350,000 people emigrate with government support to countries such as Canada, New Zealand, and Australia. In the early 1960s, rapid economic growth sets in and, all of a sudden, the Netherlands needs all the workers it can get. Demand is particularly great in the manufacturing industries. For that reason, companies such as the Hoogovens steelworks and Philips start to look abroad. Employers want temporary workers, hence the name “guest workers”.

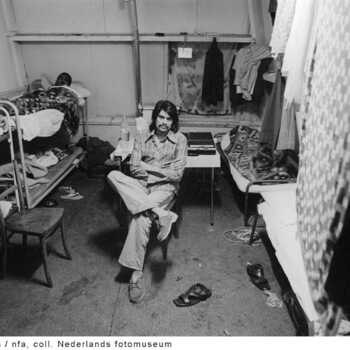

Most of the initial workers to arrive in the Netherlands come from Italy, Spain, Greece, and Yugoslavia. Most of them are men. A recruitment agreement with Turkey in 1964 prompts Turkish workers to take their lead and five years later, Moroccan workers follow suit. In some cases, the Dutch government sends an “inspection committee” to collect workers in Morocco. A majority of the migrants live and work in the industrial hubs, such as the Port of Rotterdam and the textile region in the eastern part of the country. Many of them do heavy labour, put in long hours, and live under frugal circumstances.

From temporary to permanent

In the early years, the new labour forces are welcomed with open arms. After a while, however, some of the local populations make it quite clear that their presence is not appreciated. The government does not encourage them to settle down: the idea is that the workers will only be here for a limited period of time. In actual practice, things turn out differently. Employers continue to extend contracts until the recruitment of migrant workers is officially terminated in the 1970s, when manufacturing industry starts to decline. In the 1980s, the impact of the shrinking world economy is felt particularly strongly among these groups. Many workers remain in the Netherlands, especially when the Family Reunification Act (1974) opens up the possibility to send for their families.

From the 1980s onwards, the Dutch government has been working on an integration policy that continues to this day. Must newcomers adapt and blend into the majority culture, or can integration be achieved whilst retaining one’s own identity? Or is integration a combination of these two views?

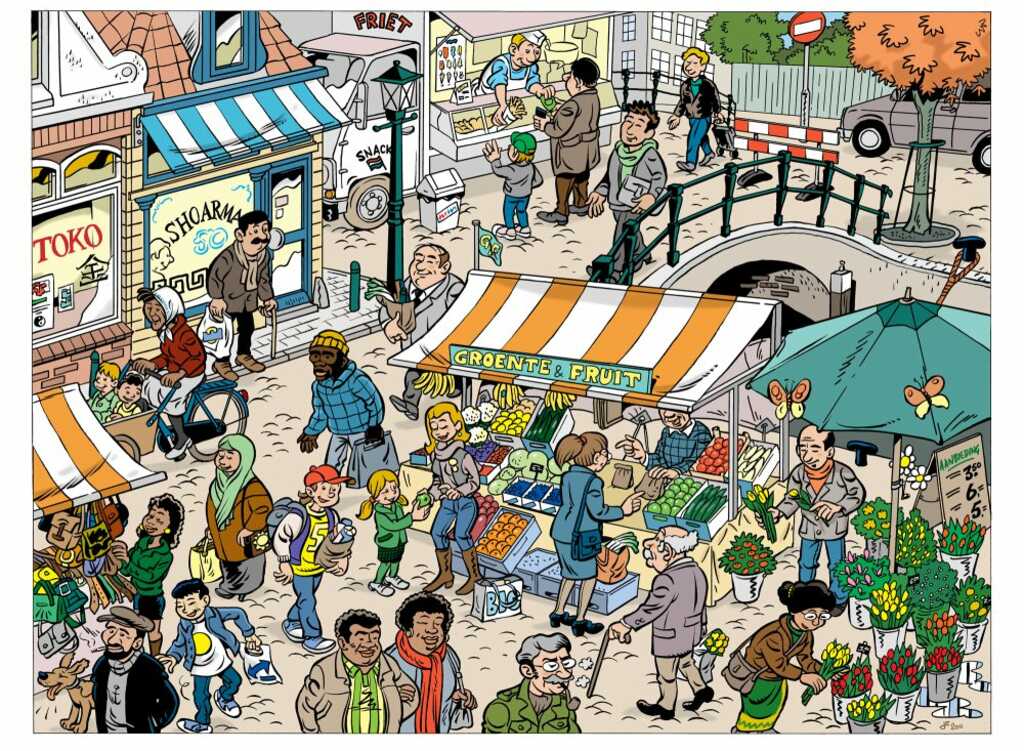

The multi-cultural society

With the arrival of this large group of workers, the Netherlands has once more become an immigration country. Apart from the influx of immigrant workers, the Netherlands grants asylum to political refugees, as do many other European countries. In addition, migrants from Surinam and the Antilles also settle in the Netherlands. Within the European Union, the Netherlands eliminates its borders, resulting in the immigration of workers from eastern Europe.

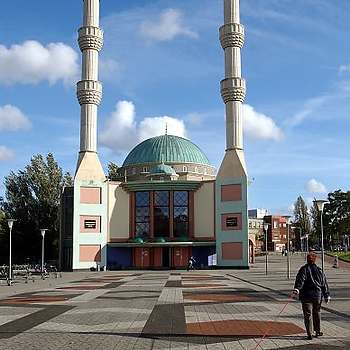

The various migration flows give rise to a heated political debate on the relationship between society, culture, and religion. This debate is exacerbated by the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 in the United States of America. A key issue is the position of Islam in Dutch society. A recurrent question in this respect is what exactly “Dutch citizenship” entails, and to what extent the Netherlands is receptive to newcomers.

Apart from the societal discussion, migrant children are prone to an accelerated individualisation process. Such children are found in all walks of life. Yet poor socio-economic conditions hamper many migrants in successfully moving up in society, whilst many of them are faced with discrimination in terms of participation in the labour market.

Children of immigrant workers are investigating how their parents’ migration is impacting on their life. In 2018, Murat Isik wins the Libris Literature Award with his novel Wees onzichtbaar [Be Invisible], in which he tells the migration story of his Turkish family in southeast Amsterdam. Such a coming of age account gives this generation a sense of belonging and fosters connection.