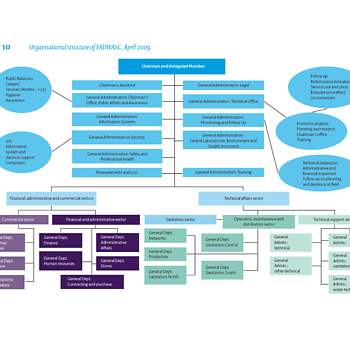

The gamechanger of this phase has been the creation of the Holding Company for Water and Waste Water (HCWW) that regrouped subsidiary companies in each governorate, in the case of Fayoum FADWASC (Fayoum Drinking Water and Sanitation Company) and the subsequent release of the many investments in the NOPWASD pipeline (some 6 WWTPs and 25 collection systems upstream), an abundance in investment funding in water supply and sanitation by the GOE, and a very strong increase in staff (3,000 employees). We note with hindsight that FADWASC was struggling throughout the project period to come to terms with these developments.

FADWASC had become a large organisation, housed in a new high-rise office building (that was unfortunately torched during the “Egyptian Revolution”). Many of and the “junior engineers” that helped us to start Phase I, were now senior managers. It was run as subsidiary of the HCWW and had to operate under different managerial concept reporting systems developed by USAID. The EMP concept that worked successfully during Phase III & IV, commanded less and less attention from the Chairman who was nominated by the HCWW (and frequently replaced).

FADWASC had to rethink its business processes as Sanitation became important business. The lessons of the One-Shop-Stop for drinking water paid off handsomely. New sewer connections, comprising HDPE collection chambers and PVC piping, were realized on an industrial scale by contractors with pre-financing through the Sewerage Revolving Fund, created during Phase IV, resulting in significant savings (up to some 40% in comparable projects in Egypt) and accelerated starting up of the new systems.

Maintenance became a hot item due to high maintenance demand of wastewater installations. New maintenance concepts were tested in the WWTP of Sennoures resulting in the development of a comprehensive Computerised Maintenance Management System (CMMS) that was finally applied in 5 WWTPs, 1 DWTP (NEAT) and 5 Districts. Maintenance Teams turned out to be highly effective in the rehabilitation of existing plants. The system was rolled out to 5 WWTPs in Middle-Egypt (with assistance of the USAID-financed sister project) and was made available to the entire sector. WWTP operations further were streamlined into an Operation System with the valuable assistance of the Dutch Waterboard HDSR in a twinning arrangement.

The UASB Demonstration Plant in Sanhour successfully demonstrated the possibilities of this technology in Egypt by its ease of operations, its low operation costs, and small footprint, making it very suitable for extending existing WWTPs, as was the case in Sanhour. General acceptance was constrained by the dysfunctional existing secondary treatment (trickling filter). Replacement of the Trickling Filter has been started but come to a halt in the aftermath of the Egyptian Revolution.

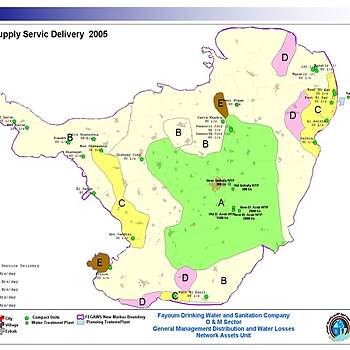

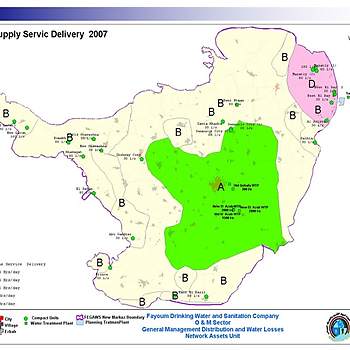

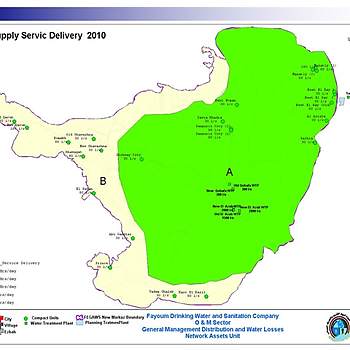

Distribution, however, remained plagued by bottlenecks, although important progress had been realised (see the service delivery maps). An impact analysis of the IOB demonstrated that more than 95% of the population received drinking water of good quality but that serious contamination problems existed in the service areas with intermittent supply, forcing the consumers to store water under adverse conditions. The bottlenecks demonstrated a lack of understanding caused by a complex of problems dealing with the diminishing role of the Planning Department, the decision-making processes for investment (with Cairo an uncertain factor), and the abandonment of the hydraulic model developed in Phase I. A new model developed during Phase V demonstrated that many bottlenecks that could have been addressed with small investments.

Network maintenance was strengthened by combining the maintenance concepts developed in sanitation, the experiences gained in the UFW reduction programme in Phase IV and GIS. The Network CMMS, inspired on the original that only covered E/M equipment, was developed and installed in the Distribution Districts, Maintenance Engineers nominated, and network information of the GIS made available on base maps, thus ensuring validation and systematic updating of the GIS.

This project was also successful by the active role of the Royal Netherlands Embassy, institutionalised in the Project Advisory Committee. It was here that the NEAT project was conceived with direct financing to the Governorate, bypassing NOPWASD. The PAC provided momentum to the Project. It is only appropriate that in the last phase of this project the second phase of the New El Azab Treatment Plant was commissioned in 2010 in a similar arrangement as the first phase, raising the total capacity of NEAT to 5,200 I/s.

The Egyptian Revolution in 2011 prevented Phase V to complete its mission as intended. It was successful in reaching its physical targets in terms of connection but had limited success in transferring the “Fayoum experience”. New management concepts were introduced in the sector, mainly orchestrated by USAID and to some extent GTZ, and the Fayoum experience did not fit in that picture. The project was successful in promoting its concept of maintenance management, partly due to the collaboration with USAID.