In the recent decade Dutch development policies and programs on food security better recognized and supported the role of women in agriculture and food security, including within sustainable resources management and climate adaptation and mitigation. The Policy Document on Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation of May 2018 (Investing in Global Prospects) emphasized the Dutch commitment to Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment. This policy document recognized that “Investing in women means investing in development and growth”, also declaring that promoting gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls (SDG5) is a goal in all components of policy of the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Development. This has to be achieved by taking further steps in gender mainstreaming and making gender results in the different policy areas more transparent. This policy is reflected in the Theory of Change on Food Security of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Trade and Development (autumn 2018), which states that the implementation of the Dutch food security policy should be gender-responsive and nutrition-sensitive, paying attention to gender issues in food systems and recognizing that access to land, productive resources, credit, and markets is a major constraint, especially for women and youth. More decision-making and control by women is needed to increase food production, for the intake of more nutritious food and for better spending of income.

The emphasis on international trade and development cooperation policies and instruments (“Aid and Trade”) also meant more attention towards developing female entrepreneurship in agri-business and other sectors, through partnerships with the Dutch private sector and establishing e.g. incubator centra for young starters to develop innovative businesses.

However, there are still many obstacles and challenges to gender equality and the empowerment of women within the agricultural sector. These are often more related to social, cultural and institutional factors rather than technical problems. Many of the key constraints earlier identified in this paper still prevail. This means that the 2010 FAO study on “Women in Agriculture” -as part of FAO’s ‘State of Food and Agriculture’ of 2010- remains actual as still many gender inequalities within food security are not -or insufficiently- addressed. The IFPRI/CGIAR report on Advancing Gender Equality in Agricultural and Environmental Research well identifies current priorities to move towards more gender equality within agriculture and food security, such as women’s empowerment through value chain participation, nutrition-sensitive agriculture, and women’s agency in climate change interventions, whereby striving for gender transformative change remains imperative.

An example of a recent Dutch funded project, the Blue Gold Program, illustrates that conscious efforts to gender mainstreaming can contribute to more gender equality and empowerment of women, thereby also better achieving the project’s overall objective of poverty reduction and economic growth.

Blue Gold and empowering women farmers

The Blue Gold Program (BGP) was a poverty reduction and economic development program in the south-west coastal region of Bangladesh with a central focus on water management and agriculture, implemented between 2013 and 2021. The program was funded by the governments of Bangladesh and the Netherlands, and implemented by the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) and the Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE). Blue Gold operated across 119,000 ha in 22 polders in 4 districts where an estimated 200,000 households benefited directly from its interventions. The latter included the improvement of water management infrastructure, the strengthening of community-based Water Management Organisations, the improvement of agricultural practices using opportunities created by improved water management, and linkage development with markets and service providers.

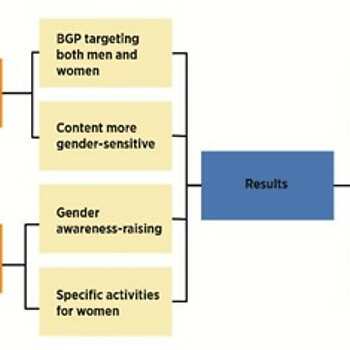

Gender mainstreaming was foreseen in the design of the program. In the initial years this was translated as participation of women in activities, such as in Water Management Groups (women constituting 43% of its members) and in Farmer Field Schools (women as 62% of all FFS participants). In later years, also program content was made more gender sensitive, including by addressing gender norms, such as promoting women’s equal involvement in decision-making, promoting women’s leadership, and creating awareness on sharing domestic work. Gender mainstreaming was accompanied by selected specific gender activities, such as gender (awareness) training, see the figure in box 2 above.

About 55,000 women farmers participated in Farmer Field Schools (FFS), either conducted by DAE or by the TA team, enhancing their technical knowledge and skills, as well as improving access to inputs and markets. Many lessons were learnt; some specific lessons regarding gender and agriculture were:

- There were hardly any FFS or training topics that were only of interest to men farmers or to women farmers. Training and FFS participants should be selected based on their interest, not just on their gender.

- All modern technologies disseminated by Blue Gold had both male and female adopters.

- Women farmers were often more conscientious in applying learnings than male farmers.

- Women’s contribution to increased agricultural production clearly contributed to increased production and income, and to achieving Blue Gold’s overall objective of poverty reduction.

- Women farmers, who increased their knowledge and productivity, often gained more respect, with husbands more involving them in decision-making on agricultural planning and expenditure. As one male farmer said this led to “more peace in the household”.

- Women farmers were highly interested to learn about marketing; the use of mobile phones facilitated contacting traders and service providers.

- Women farmers became more empowered: economic empowerment, increased confidence, more women’s leadership (e.g. as Resource Farmers or Farmer Trainers), increased women’s social networks and mobility, evidence of some changes in gender norms, and women’s well-being and quality of life improved, e.g. by poverty reduction and less domestic violence.

Main source: Chapter 24 on Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment of the Blue Gold Lessons Learned Report.

Specific Blue Gold materials on women farmers:

- Horizontal learning empowering women: sharing poultry rearing successes

- Women’s empowerment through homestead farmer field schools

- Women in collective actions and market linkages: increasing benefits and empowerment

- Feminization of agriculture, women’s workload and sharing domestic work

Practical recommendations for mainstreaming gender equality in food security projects, as derived from the Blue Gold Program:

- Conduct a gender analysis, including assessing specific needs of women farmers, and use this as input for project design (activities and indicators).

- Realise that terms as ‘farmer’ and ‘entrepreneur’ include both men and women. Avoid gender-stereotyping and do not forget female headed households.

- Include a package of specific gender activities to complement and support gender mainstreaming.

- Quotas work if accompanied by other measures as awareness raising.

- Pay attention to women’s workload to avoid overloading. Promote sharing domestic and care work and time saving technologies and measures.

- Gender expertise within the TA team is crucial, female (field) staff important (also as role models) and practical gender training of project staff is necessary.

- Commitment of project management is a main success factor!

It is crucial that “Closing the gender gap for development” remains on the political agenda in the future. Striving for more gender equality and empowerment of women in agriculture and food security is essential both from a human rights point of view and for better economic growth.