Welfare Approach

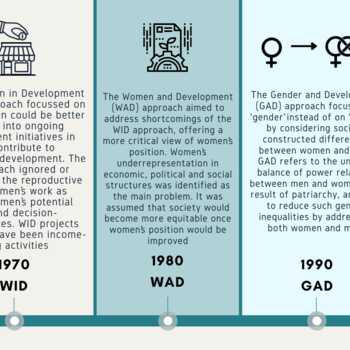

From the 1950s onwards the ‘welfare’ approach to development cooperation treated women as vulnerable groups and passive aid recipients, needing practical advice and aid for their traditional, domestic and reproductive roles. Around the 1970s this started to change. It was gradually recognized that also women needed to be integrated in ongoing development initiatives for ‘modernization’. Existing unequal structures were still accepted.

Women in Development (WID)

The term ‘women in development’ came into use in the early 1970s, after the publication of Ester Boserup's publication Women's Role in Economic Development in 1970. Boserup was the first to analyse the changes that occurred in traditional agricultural practices as societies became ‘modernized’. She examined the differential impact of those changes on the roles of, and the work done, by men and women.

The WID perspective was closely linked with the ‘modernization paradigm’ which dominated mainstream thinking on international development during the 1960s and into the 1970s. The WID approach began from an acceptance of existing social structures. Rather than examine why women had fared less well from development strategies during the past decade, the WID approach focussed on how women could be better integrated into ongoing development initiatives. In other words, ‘women in development’ or ‘WID’, is understood to mean the integration of women into global processes of economic, political and social growth and change.

The WID approach tended to be a-historical and overlooked the impact and influence of class, race and culture (Mbilinyi 1984; Lycklama à Nijeholt 1987). Furthermore, it did not recognize the contribution of more radical or critical perspectives such as ‘dependency theory’ (Galtung c.s.) or Marxist analyses. The WID approach tended to focus exclusively on the productive aspects of women's work, i.e. women’s potential to contribute to economic development. The reproductive side of women's lives as well as women’s political and decision-making roles were largely ignored or minimized. WID projects typically have been income-generating activities where women were taught a particular skill or craft. Organizing women into marketing and handicrafts cooperatives were also rather popular. Although the WID approach gained prominence, the underlying “welfare outlook” often remained part and parcel of development projects, whereby women were taught aspects of hygiene, literacy or child care (Buvinic 1986).

Women and Development (WAD)

Based on the lessons learnt from the WID approach, various shortcomings became visible. The WAD approach aimed to address these, evolving from the WID approach in the late 1970s / early 1980s. In essence, the WAD approach begins from the position that women have always been part of development processes. Women did not suddenly appear in the early 1970s with the WID approach. The WAD approach offers a more critical view of women's position than the WID approach does, but it still failed to undertake a full-scale analysis of the relationship between patriarchy, differing modes of production and women's subordination and oppression. The WAD perspective implicitly assumed that women's position will improve if, and when, society becomes more equitably organized. Rather it was the underrepresentation of women in economic, political and social structures that was identified as the primary problem. WAD was operationalized by taking women more serious as actors in development, for example, by consulting them more often during project design and implementation.

Gender and Development (GAD)

The GAD approach, which was developed during the 1980s, stepped away from both WID and WAD. This meant a shift from focusing on women only to focusing on ‘gender’, by considering socially constructed differences between men and women. This gender approach intends to address gender gaps and enhance gender equality. Gender equality exists when men and women, and boys and girls, are attributed equal social value, equal rights and equal responsibilities, whereby men and women have equal access to the means (resources, opportunities) to exercise those rights and responsibilities. This means that rights, responsibilities and opportunities do not depend on whether someone is born male or female. Founded in socialist-feminist ideology (Rathgeber 1989), the GAD approach therefore also welcomes the potential contributions of men who share a concern for issues of equity and social justice.

The GAD approach does not focus only on either productive or reproductive aspects of women's lives. Rather, it analyses the nature of women's roles (vis-à-vis that of men), both inside and outside the household. It rejects the separation between the public and private domains which commonly had been used as a mechanism to undervalue family and household maintenance work, i.e. the work traditionally done by women. In essence the GAD approach thus refers to the unequal balance of power between men and women as a result of patriarchy, with the aim to reduce such gender inequalities.

The GAD approach sees women as ‘agents of change’ rather than as passive recipients of development. It stresses the need for women to organize themselves for a more effective -political- voice to address inequalities. The importance of both class solidarities and class distinctions were recognised. However, from the GAD perspective it was argued that the ideology of patriarchy operates within, and across, classes to oppress women.

An interesting shift that happened between WID/WAD and GAD was the change in language from dealing with 'women' in the context of development, to 'gender'. Some critics argued, among them Nighat Said Khan, founder of the Women’s Action Forum (Lahore, Pakistan), that “…this shift to a focus on gender rather than on women became ‘counter-productive’ because the discussion shifted from ‘women’, to ‘women and men’ and, finally, back to ‘men’” (as cited in Baden & Goetz, 1997, p.6). However, the essence of the GAD approach is about addressing the unequal power balance between men and women to achieve gender transformative change. This means that relationships between men and women that are based on patriarchy and traditional gender norms need to change. To achieve such changes, the engagement of both men and women is equally important as is the empowerment of women.

On masculinities: Starting in the 2000s the disappointing results of the policies to improve women’s positions brought questions of men’s control over technology (and power) newly to the fore, and with it questions of masculinity and race. This re-inspired feminist scholars to consider the whole dynamic of men’s domination of women in society (Liebrand 2022). Masculinities nowadays refer to the set of attributes, norms, values, behaviour patterns and attitudes that are characteristic of men in a particular society at a given time. It implies specific -and restrictive- expectations regarding men’s roles and behaviour in society, suggesting that men -as well as women- will benefit from relaxing male gender roles and behaviour patterns. Networks as MenEngage are exploring how patriarchal masculinities maintain and deepen injustices. They seek to identify ways of challenging and transforming them, thus supporting movements for gender justice and women’s and LGBTQI+ rights. (Also see: Interview Mushfiqua Satiar: Gender-based violence: a tough problem)

The gender policy of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs

As discussed, a significant shift took gradually place from WID, to WAD and to GAD. In this process the concept of gender was introduced, referring to the socio-cultural aspects of being a man or a women, as opposed to sex, which refers to the biological aspects. These distinctions were already made in the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW, 1979), by the Beijing Platform of Action (fourth UN World Conference on Women, 1995) and in the Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security of 2000.

From the end 1980s onwards the Dutch development policies also shifted towards gender equality and women’s rights. Initially the focus was on women’s autonomy (see box 1), violence against women and trafficking in women, next to gradually recognizing the importance of male-female relationships. MFA’s New Agenda for Aid, Trade and Investment of April 2013, A World to Gain, designated women’s rights and gender equality as a policy priority to be pursued throughout all foreign policy. This meant that in principle all projects and programmes had to contribute to gender equality by either:

- Reducing social, economic or political power inequalities between women and men, girls and boys

- Ensuring that women benefit equally with men from the activity, and/or

- Compensate for past discrimination.

MFA’s policy note Investing in Global Prospects of the Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation (BHOS) of 2018 recognized that investing in women means investing in development and growth. This policy note reinforced the commitment of the Netherlands to promote gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls as a goal in all components of MFA’s policy, explicitly referring to Sustainable Development Goal 5 (SDG5) on gender equality. This agenda has four targets:

- Increase women’s participation in political and other decision-making and women in leadership

- Increase economic empowerment and improve the economic climate for women

- Prevent and eliminate violence against women and girls

- Strengthen the role of women in conflict prevention and peace processes, and protect them in conflict situations.

Recent developments within Dutch development cooperation include additional attention to inclusiveness and intersectionality (i.e. analysing gender simultaneously with other social differences such as ethnicity, class, age, and sexuality), though this does not figure yet consistently in key policy documents (IOB 2021).

Although progress has been made over the years, the process of ensuring gender equality and empowerment of women will need continued attention in the future. Besides, backlashes in gender equality and women’s rights also occur, both in developing countries (e.g. stricter abortion legislation), but also in EU member states (see a research report of 2018).

Operationalization of the Dutch gender policies

The international gender policy of MFA is implemented by a two-track strategy. The first track provides support to women’s organisations and/or gender equality initiatives with earmarked funding from stand-alone gender budget lines. These are projects and programmes that address gender inequalities and women’s rights as a main objective, also called ‘gender-specific’ projects. The second track is gender mainstreaming, which is the systematic integration of gender issues in all projects, programmes and policies.

The Netherlands was an early adopter of the two-track strategy, way before the global adoption of this dual strategy in the 1995 Platform for Action (IOB 2015, quoted by Dubel 2016). In 1999, however, the Netherlands’ international gender policy focused merely on gender mainstreaming, at the expense of funding of gender-specific projects. Women’s organisations in developing countries had seen their resources decline after 1999, at a time when the realisation of Millennium Development Goal 3 (MDG3) on gender equality was lagging behind. This was reversed in 2007 with the so-called Schokland agreements, “recognizing that abolishing the stand-alone budget for women’s rights and gender equality … had not been a wise decision”, also because “gender mainstreaming was not living up to its promises”. As a response the MDG3 Fund (2008-2011) of €77 million was established aiming to realise concrete improvements in rights and opportunities for women and girls in developing countries. Grants to 45 applicants were provided, mainly to women’s organisations. The MDG3 Fund was followed by the FLOW1 (2012-2015) and FLOW2 (2016-2020) Funds (Funding Leadership and Opportunities for Women).

The international gender policy of 2011 reaffirmed the dual approach, assuming that the tracks would reinforce each other.

Gender mainstreaming in practice

The IOB report of 2015 Gender Sense & Sensitivity evaluated the international gender policy between 2007 and 2014. It found that MFA had not shown sufficient leadership and had lacked the knowledge, skills and means to really put the Dutch gender mainstreaming policy into practice. In 2021 the IOB published a follow-up report specifically on gender mainstreaming. Although steps were made, a main finding was that gender was still too often seen as synonymous with women. And consequently, gender mainstreaming insufficiently dealt with addressing power relations between men and women or with more fluid gender identities as trans-gender or non-binary identities. This report found that 70% of 95 reviewed projects engaged women and/or girls, but only 15% discussed transformative issues such as changing gender norms. Hence, there was still ample room for improving gender mainstreaming, as also demonstrated by the recommendations in this IOB report of 2021.

Adhering to the criteria for the OECD-DAC gender equality policy marker of December 2016 (see explanation under gender tools) is an important step towards effective gender mainstreaming. The minimum recommended criteria for gender mainstreaming in projects/programmes, which need to be met in full, are:

- A gender analysis of the project/programme has been conducted

- Findings from this gender analysis have informed the design of the project/programme

- Presence of at least one explicit gender equality objective backed by at least one gender specific indicator

- Data and indicators are disaggregated by sex where applicable

- Commitment to monitor and report on the gender equality results achieved by the project in the evaluation phase.

Effectiveness of gender-specific projects versus gender mainstreaming

It is widely recognized that gender-specific (or gender stand-alone) projects or programmes have usually been more effective in achieving gender equality results than gender mainstreaming. However, considering the much larger scale of opportunities for mainstreaming vis-à-vis the budgets for gender-specific interventions, it is obvious that effective gender mainstreaming is dearly needed to achieve gender equality, such as defined by SDG5 ‘Achieve Gender Equality and Empower all Women and Girls’, set for 2030.

The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) has a similar two-track approach as the Dutch MFA. The findings from the report on Effectiveness of Swiss international cooperation in the field of gender equality 2007-2016 are therefore also interesting for the Dutch situation:

- 73% of the reviewed gender-specific projects contributed to some level of structural gender change, against 31% of the projects with gender as a transversal theme i.e. mainstreaming gender. Thus gender-specific projects performed best, but gender mainstreaming can also work!

- Projects implemented over a 10 year period (2007-2016) were reviewed; over time, the gender effectiveness scoring for projects with gender mainstreaming significantly improved.

- Good project design was found as a key to success, based on gender analysis and including specific gender activities.

- Other success factors were the commitment to gender by SDC, the commitment of (project) management, adequate gender capacity building, access to gender tools, guidance sheets and checklists, and gender platforms as a learning mechanism on gender.

Gender diplomacy

The above discussed dual approach is complemented by ‘gender diplomacy’ to improve the enabling environment for achieving more gender equality. The Netherlands is an international advocate to advance gender equality and the empowerment of women (MFA 2018). This is addressed through diplomatic efforts, policy dialogues, involving women and girls in political consultations and promoting the presence of women at negotiation tables.

Further reading:

- Rathgeber, E.M. (1989). WID, WAD, GAD: Trends in Research and Practice.

- IOB (2021). Gender mainstreaming in the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Beyond ‘add women and stir’?

- IOB (2015): Gender sense & sensitivity: Policy evaluation on women's rights and gender equality (2007-2014)

- IOB (1998): Vrouwen en Ontwikkeling; beleid en uitvoering in de Nederlandse Ontwikkelingssamenwerking 1985-1996

- World Bank (2001):Engendering development: through gender equality in rights, resources and voice

- SDC (2018). Report on Effectiveness: Swiss international cooperation in the field of gender equality 2007-2016. Bern.

- OECD (2016). Definition and minimum recommended criteria for the DAC gender equality policy marker.

- MFA (2018): Investing in Global Prospects, Policy Document of the Minister of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation

- MFA (2013). A World to Gain: A New Agenda for Aid, Trade and Investment, Policy Document, April 2013.

- Dubel, Ireen (2016). GRF Response to Evaluation of NL Gender Policy

- Boserup, Ester (1970). Woman's Role in Economic Development. Available in the library of International Institute of Social Studies (ISS).

- Mbilinye, Marjorie (1984). ‘Research priorities in women’s studies in Eastern Africa’, Women’s Studies International Forum, Vol 7, Issue 4, pp 289-300.

- Lycklama à Nijeholt, Geertje (1987). ‘The Fallacy of Integration: the UN Strategy of Integrating Women into Development Revisited’, Netherlands Review of Development Studies, Vol. 1, pp. 23–37.

- Buvinic, M. (1986). ‘Projects for women in the Third World: explaining their misbehaviour’, World Development, Vol 5 No 15.

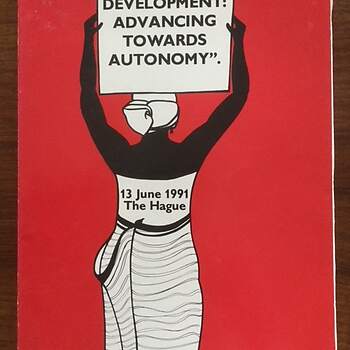

- MFA (1992): Women in Development: Advancing towards Autonomy. Report on a seminar on Women in Development held in The Hague on June 13, 1991. The Hague. Soon to be available in the NICC collection.

- Liebrand, Janwillem (2022): Whiteness in Engineering – Tracing Technology, Masculinity, and Race in Nepal’s Development. Himal Books, Nepal.

- Website MenEngage