1972-1980

Bangladesh saw the Netherlands as a natural and obvious partner for the water sector, in view of the latter's knowledge and experience with issues related to water and land. In 1975, possibilities for Dutch involvement in the water sector in Bangladesh were identified in three essential respects:

- relatively small early implementation projects that could be quickly executed and would bring immediate bring benefits (this with a view to the dire situation the country was in)

- a project in the western part of the delta, geared towards the specific characteristics of that region

- a project in the eastern, dynamic section of the coastal zone, the Land Reclamation Project (LRP). This timeline focuses on the activities in the eastern delta.

In May 1977, an agreement on technical cooperation was concluded between Bangladesh and The Netherlands. The Land Reclamation Project (LRP) started later that year. The main features of the LRP were institutional development (the formation of action groups among the landless); studies of land reclamation methods; settlement of new char land; and the development of agricultural production. The LRP marked a departure from the dominant sectoral approach to coastal development in the seventies and took a first step towards an integral strategy to address the various aspects of people's livelihoods.. It was conceived as a pilot project for the planning and implementation of new land reclamation projects.

1981-1990

During this period, the LRP developed one polder (by constructing embankments, sluices, drainage channels and cyclone shelters) and generated a substantial number of studies (on topics such as methods to promote accretion, agricultural research, and the feasibility of creating additional chars). It started a process of land settlement, by organizing landless groups and allocating land to them. An appraisal mission in 1990 found that the project combined too many objectives, which were not necessarily compatible, and had therefore becme too complex. The project was discontinued and two follow-up projects were formulated: the Char Development and Settlement Project (CDSP) for the land-based activities and the Meghna Estuary Survey to collect knowledge about the physical processes in the Bay of Bengal.

1991-1999

The focus of coastal development gradually shifted in focus over the decades, with a general trend towards an integrated, multi-sectoral approach, often called the Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM)-concept. When the LRP was terminated, preparations began for the CDSP. The ICZM concept guided the formulation of the project and was reflected in the institutional framework. Apart from developing an integrated strategy, the project had three central objectives:

- poverty alleviation

- participation

- improving the position of women.

The CDSP commenced in 1994 and had the following components:

Unprotected and protected areas: Government policy stipulated that new land would be brought under the control of the Forest Department, whose task would be to stabilize the land. Once this had been done, a decision would be made on whether to leave the land unprotected or, if it was high enough, to establish a polder by constructing embankments and drainage sluices. A polder provides security and the salinity of the soil gradually decreases, so criteria for empolderment developed in the course of the project.

Land settlement: By law, all newly emerged land belonged to the government and ultimately had to be distributed to landless households, with a maximum of 1.5 acres per household. This principle was applied during the project and helped simplify the settlement process (the procedures for obtaining a title to the land).

Forestry development: In the earliest phases, mangroves helped to accelerate the land formation, and later contributed to greater safety, improved ecological conditions and a better economic situation. Using social forestry methods, support was procided for the planting of trees to provide fruit, timber and fodder along roads, on the slopes and in front of embankments.

Infrastructure: Obviously, char lands were devoid of any meaningful infrastructure, The CDSP addressed this by constructing basic infrastructure for water management, mobility and social needs (e.g. sluices, drainage networks, roads, cyclone shelters, community ponds, drinking water, sanitation). Most cyclone shelters were used as school buildings.

Agriculture: farmers received assistance in changing their cropping patterns and cropping intensity (from single crop to double crop areas) and adopting modern crop varieties (higher crop yields).

Institutions at grassroot level: At the outset, project areas were practically barren as far as the institutional landscape was concerned. To stimulate cohesion among the settlers and help facilitate planning and implementation of interventions, field-level groups were formed for- water management and social forestry groups, as well as farmer forums and tubewell user groups. The latter groups consisted exclusively of women, while efforts were made to ensure 50% female participation in the other groups.

Institutions at national level: The approach taken in designing the institutional set-up of the project was one of common planning, followed by individual implementation: each institution would do what it does best, with separate money flows for each of them. Realization of such a set-up hinged on its proper accommodation in the formal planning procedures of the Bangladeshi government. This led to an overarching Project Concept Paper for the project as a whole and individual Project Proformas for each of the sectors. Mechanisms were established for coordination at national and district level.

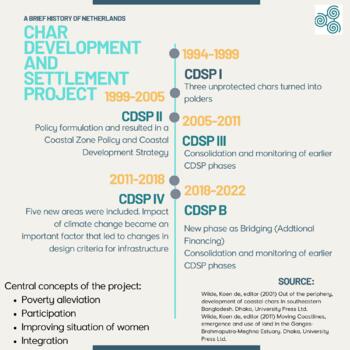

CDSP I ran from 1994 to 1999, with the Bangladesh Water Development Board as lead agency (for all water management-related infrastructure), the Local Government Engineering Department (for internal infrastructure such as roads, bridges and cyclone shelters) and the Ministry of Land (for the issuing of land titles) as participating agencies. Local NGOs were involved for activities complementary to the work of the governmental institutions. Three unprotected chars were transformed into a polder. These chars were already illegally occupied by households from neighboring areas, mainly because they had lost land and homesteads due to erosion. This made the process of land settlement more complicated. On a more positive note, useful experience was gained with the creation of field0level institutions, especially with the water management groups.

When CDSP I ended in 1999 it was impossible to foresee that the project would be extended three times over the next 22 years, and would now even be in a bridging period for a fifth phase. After each phase the project has been deemed to be sufficiently effective to commence preparations for a further project. The morphological conditions mean that the formation of new land is a continuous process. Feasibility studies have successively identified new areas where interventions can be implemented in a succeeding phase.

1999-2005

Following preparations in the late nineties, the Dutch-supported Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) project started in 2000. This project was devoted to policy formulation and ultimately resulted in a Coastal Zone Policy and a Coastal Development Strategy, which were adopted by the Bangladeshi government in 2005 and 2006 respectively. During the intervening years, there was an active exchange of views and information between between the ICZM and CDSP II projects.

For CDSP II (1999-2005), the number of partnering government agencies was expanded to five, with the Department of Public Health Engineering (drinking water and sanitation) and the Department of Agriculture Extension also becoming involved in the project. Interventions were planned and undertaken in eight additional chars, including two islands, based on a more regional approach than in the first phase. A new feature was that the project included unprotected areas that remained unprotected, with an adapted set of interventions.

An appraisal mission recommended limiting the expansion of the number of areas covered by the projectand devoting more attention to consolidating the achievements of CDSP I and II in the next phase.

2005-2011

Consequently, CDSP III (2005-2011) concentrated on consolidating and monitoring earlier phases of the CDSP and covered only one additional area. The Forestry Department was the sixth Bangladesh agency t be invited to join the projecr. The NGOs were no longer contracted and coordinated by the Dutch side, but by BRAC, a large national NGO. The input from foreign consultant was reduced. A Bangladeshi consultant was appointed to lead the technical assistance team (in previous years the Team Leader was the only permanent Dutch representative), with intermittent support and supervision from a Chief Technical Adviser from the Dutch side. Technical input from foreign consultants was also less frequent, with a bigger role for Bangladeshi consultancy firms.

2011-2022

The UN's International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) joined the Dutch government as a development partner in CDSP IV (2011-2018). Five new areas were included, all of them selected on the basis of feasibility studies carried out in the previous phase. The interventions were implemented by the same six government institutions and four NGOs. The impact of climate change became an important factor, leading to a review of the design criteria for infrastructure. In 2017, for example, the Bangladesh Water Devolepment (BWDB) revised the criteria and demanded the construction of higher and more robust embankments.

Erosion of the coastline impeded the progress of the construction of embankments, thus increasing the need for a flexible approach to the desing of infrastructure and even more attention to the methodology of forecasting future morphological developments.

An important development was the approval of the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 (formulated with Dutch assistance) by the Bangladesh government in 2018. Of particular importance for the future of char development were the topics of integrated spatial planning, coastal land accretion and the optimal use of coastal land. Relevant proposals in the list of investments concerned efforts to reclaim land by constructing cross dams, the continuation of CDSP in a new phase, an offshore integrated reclamation and development projectm and further studies of the morphological dynamics of the Meghna estuary, particularly in relation to the stability of chars. In the light of uncertainties such as climate change and socio-economic developments in the country, the plan rightly stressed the importance of adaptive, flexible strategies. Such an approach requires strong institutions and a broad and reliable data-base. Institutional strengthening and knowledge development are therefore overarching priorities for the bridging period ahead of a possible fifth phase of CDSP, in line with proposals in the Delta Plan which could include four new chars covering 11500 hectares.

Conclusion

Over the nearly fifty years of collaboration on issues of land and water, the cooperation between Bangladesh and the Netherlands can be characterized as cordial and productive. Although at times the process of gaining administrative approval of successive phases of CDSP took longer than expected, it was never due to differences of opinion on approaches and content. On the contrary, the policy context for char development was consistently favorable on both sides. The recognition in both countries that climate change and coastal development are closely interlinked made the case for mutual support of projects such as CDSP even more compelling.

At the end of 2021, a quick scan of the reach of CDSP since its inception in 1994 painted the following picture: 17 chars/polders with a total gross area of 63,000 hectares, with a population of 472,000 in 75,500 households (these figures do not include the upstream area benefitting from improved drainage). In all the project areas together, just under 35,000 land titles were issued to landless households. Analysis of the economic and financial results show that the investments were justified, particularly in terms of increased agricultural production. In the case of CDSP, the combined interventions, planned and implemented by a multitude of government departments and NGOs, have led to the transformation of a number of coastal chars with substantially improved, much more secure livelihoods for the settlers.

As far as the central goals of the project are concerned:

- Integration: The common planning, individual implementation principle worked satisfactorily. The number of partner government agencies rose from three in CDSP I to six in CDSP III and IV. NGOs were involved in complementary activities and were members of the coordination mechanisms at different levels.

- Poverty alleviation: The bulk of the economic benefits stem from the changes in agricultural production. In protected areas, cropping intensity roughly increased from 115 to over 200 in about ten years (100 equals one crop a year). In addition, a shift occurred from traditional to high-yielding varieties, at least doubling the original output of 1.5 tons of rice per hectare. These changes led to a general uptake of economic activities such as the development of markets and the establishment of shops, banks and other services. A rough estimate indicates that in areas covered by the earlier phases of CDSP, the percentage of poor households was reduced from 90% to 40%.

- Participation: The field-level groups, in particular the water management groups, were involved in both planning and implementating activities, and contributed to the operation and maintenance of infrastructure.

- Position of women: The membership, and usually active participation, of women in the many grassroot groups increased their social prestige. The better economic circumstances and development of skills led to diversification of income streams, helped by the greater mobility due to the road network. And while land titles are registered in the names of both the husband and wife, in the CDSP project the wife is named first on the title which strengthens her positionwomen (by allowing her to use the land as collateral for a bank loan, for instance). In fact, the project won the IFAD Gender Award for Asia and the Pacific Region in 2017, especially in recognition of its promotion of gender equality in issuing land titles to landless families.

References and read more:

Check out our chronological timeline on the cooperation between the Netherlands and Bangladesh.

CDSP I, II, III and IV reports see cdsp.org.bd tab e-library

General Economics Division (2018) Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 – Bangladesh in the 21st Century. Dhaka, Planning Commission, Ministry of Planning

Haider, Natasha and Andrew Jenkins, editors (2020) New land, new life, a success story of new land resettlement in Bangladesh. Government of Bangladesh, Kingdom of the Netherlands, IFAD, Boston, CAB International

Islam, M. Rafiq, editor (2004) Where land meets the sea, a profile of the coastal zone of Bangladesh. Dhaka, University Press Ltd.

Smedema, L.K. and A. Jenkins (1988) Desalinisation of recently accreted coastal land in the eastern part of the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh; in Agricultural Water Management, April 1988, vo. 134, nr. 1 (pp. 1-11)

Wilde, Koen de, editor (2001) Out of the periphery, development of coastal chars in southeastern Bangladesh. Dhaka, University Press Ltd.

Wilde, Koen de, editor (2011) Moving Coastlines, emergence and use of land in the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna Estuary. Dhaka, University Press Ltd.

Wilde, Koen de, Char Development and Settlement Project: experiences and reflections, in Mohammad Zaman and Mustafa Alam, editors (2021) Living on the edge, char dwellers in Bangladesh. Cham, Springer Nature