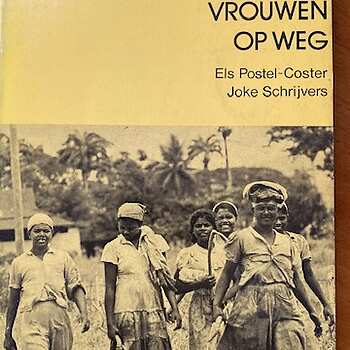

In 1975 the first International Women’s Conference was held in Mexico. This gave a new and strong impulse to the Women’s development and what we later would call Gender Mainstreaming. In the Netherlands Els Postel en Joke Schrijvers (University of Leiden) published the book, entitled “Vrouwen op Weg". This publication, literally translated as “Women on the Way” gave a major impulse to the knowledge on Women and Development.

1. Gender and Capacity Development from 1976 to 1980

In the period 1976-1980 MoFA (Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs) a “Women’s Coordinator” was appointed to coordinate “Women’s Affairs” (V&O) within the Ministry, including policy development, coordination with other donor countries and ministries within the Netherlands. In this period a major research programme on Women and Development started in Sri Lanka, Egypt and Burkina Fasso in order to formulate recommendations for policies on Women and Development. The Research and Documentation Centre for Women and Development at Leiden University was established (Onderzoek en Documentatie Centrum Vrouwen en Ontwikkeling (VENO)).

Other initiatives that matter were:

- An international MA study programme on “Women and Development” was initiated at the Institute of Social Studies/Erasmus University (the Hague)

- “Women Studies” were established at Dutch Universities.

- The Women’s Council (“Vrouwen Beraad”) of Dutch development organisations, MoFA, Joint Financing Organisations and Religious Organisations was set up. Main objective was to exchange experiences, support each other and to sensitize organisations and the ministry for women’s development.

In this period the main policies focused on poverty reduction, the economic role of women and how to lessen the triple burden and drudgery of women’s work. Financing was mainly through small scale funding through the instrument of the KAP (small scale Embassy projects”) and the so called “women’s component” within new and existing projects. (NB. remember the “add women and stir approach”)

The period of 1976–1985 was declared as the UN Decade for Women.

2. Gender and Capacity Development from 1980 to 1985

During the period 1980-1985 the Second International Women’s Conference took place in Copenhagen. The Forum for Women, with representatives of women’s organisations of developing countries took the floor and gained importance and influence.

- MoFA started to give more attention to policy development and capacity development of international cooperation policy officers and other relevant development cooperation institutes like MFOs, SNV and NUFFIC.

- MoFA started to profile itself and influence policy development with regard to WID within the international women’s movement and the UN, such as FAO, ILO and UNICEF.

- Geertje Lyclama a Nijeholt became the First Professor Women’s Studies at the Agricultural University (LU) in Wageningen and at the ISS.

Important themes in policy development and programming were lessening the burden of women’s work and strengthening economic position of women; health; attention for female headed households and women’s independence.

3. Gender and Capacity Development from 1986 to 1990

In the period 1986-1990 the Third International Women’s Conference to place in Nairobi.

Characteristic for this phase of development are:

- Increased power of the International Women’s movement in developing countries that emphasises the autonomy of women

- Introduction of the term “gender” (man/woman relationship emphasizing the unequal power balance between them)

- More attention for Violence against Women (VAW) and International Trafficking in Women.

- Gender studies become “mainstream” in research and capacity development (training). Emphasis on “what works, what needs to be done better, what is missing and what is it that we do not yet do?”

- MoFA created the first position of a gender specialist at the Dutch Embassy in New Delhi, and over the following years increased the number of gender experts at Dutch Embassies.

- In Dutch development projects growing attention is paid to women’s components in e.g. rural development programmes, drinking water and sanitation programmes and human resources development.

- Opportunities for gender training of Ministry’s officials increased.

- Emphasis on the concept of Women’s “Autonomy”. The Department of Women Studies at Leiden University was renamed from VENO to VENA.

"The scholars based at Leiden University discussed how far they could go with their critique and advice. ‘We did not want to use the words poverty and poor women, as we did not want to portray women as victims but as agents in their own right’ (C. Helleman, personal communication, August 28, 2017). They recommended development cooperation policy to act as gender equality policy. ‘Gender equality is first of all in the interest of the woman herself, but is also an indispensable link in the total development process"(Postel-Coster & Schrijvers, 1976, p. 102). In 2021, the implementation of the recommendations is still a work in progress."(source: Ireen Dubel, Tijdschrift voor Genderstudies 24(1), 2021 getiteld ‘1975 - 'Not just a year but a lifetime for women’: How Dutch engagement with ‘women and development’ questions took off’, pp. 5-23).

4. Gender and Capacity Development from 1990 and onwards…

From 1990 onwards gender policies and practice were an established part of MoFA. Gradually the attention shifted to women’s rights and sexual- and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), and women in conflict and crisis.

In 1995 the Fourth International Women’s Conference took place in Beijing. The “Beijing Declaration”, also signed by the Netherlands gave a new impulse to women’s development and capacity building.

In 2000 the UN Millennium Goals (MDGs) were adopted with #3 MDG on promoting gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.

In 2010 the first Gender Action Plan of the European Union was developed, followed by the second (2015-2020) and third (GAP III, 2020-2025).

In 2015 the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)were adopted with SDG #5 specifically on Gender Equality.

At MoFA the two pronged approach to gender includes: (i) Women’s Empowerment ; and (ii) Gender Mainstreaming. As we have seen, through the years the focus may have changed somehow, but in essence the policies remained the same. However the number of countries that received support decreased though the years. This was partly because of efficiency arguments, and also as a result of an increased attention for local ownership. India, for example, terminated the long lasting cooperation.

Embassies were asked to select four priority areas of cooperation, in consultation with government. This resulted in posting fewer thematic gender experts[2] and the gender experts that worked at DGIS were often not replaced after their retirement.

5. Gender Training and Capacity Development:

Gender training and capacity development changed through the years. In the Nineties and early 2000 thematic gender experts were trained for 3 days at a specialised agency. During the summer holidays policy officers, that were interested in gender, could apply to follow a one day “gender training” that was prepared, and implemented, by staff of the then department for gender (DSO/VR). A syllabus on gender was made available, but the voluntary nature of the training did not result in significant gains.

Nowadays to address gaps in knowledge and skills, several training options exist for ministry staff, including a general introductory training on gender, and short training sessions on women in conflict and private sector development. Participation in these training sessions, which were positively assessed, is largely voluntary, although encouraged. The findings from the IOB review call for a more hands-on training that could tailor to different audiences within the ministry. The use and awareness of the gender resource facility and pool that was designed to address shortages in gender expertise are limited.

Gender analyses are conducted to an increasing degree, also in the most recent multi-annual country and regional programmes. The quality of these analyses is variable and at country level, attention for women’s rights and gender equality does not necessarily translate into a gender mainstreaming strategy or gender equality goals. The TFVG (Taskforce Women's rights and gender equality) offers advice on how to conduct a gender analysis on its internal webpage. However, it neither systematically monitors the quality of these gender analyses nor reviews what happens.

Positive examples are there too. On the initiative of the Dutch Embassy in Kigali (Rwanda) d a local gender expertise centre was contracted to support local- and Dutch staff to increase their gender knowledge in a “tailor-made” manner. After a plenary meeting to explain the key concepts of sexe, gender and gender analysis, the staff was asked to formulate their own training needs. Based on their needs the agency then offered longer term, “hands-on” and tailor made assistance.

In Burundi, neighbouring country of Rwanda, the interest for this kind of tailor made support was also acknowledge and successfully contracted with the same agency.

These example show that leadership of Ambassadors and Heads of Development Cooperation matters.

The Royal Netherlands Embassy (RNE) at Sana’a has made serious efforts to incorporate gender needs and interests in the sectors that they support. The analysis of different needs and interests of men and women and the design of strategies to respond to them is called ‘gender mainstreaming’. This is one of the two pillars of the Dutch gender policy that aims at equal inclusion and participation of men and women in development.

This story focuses on two sectors: health and education. In RNE the initiatives and the efforts of gender mainstreaming are the task of the thematic advisors of the various sectors and the gender specialist. How have they dealt with women’s needs and interests in education and health? What did they do to involve women and men in planning and implementation of projects? What has been the role of RNE Sana’a in incorporating issues of gender equality in sectoral institutions and policies? The story wants to show in particular how the role of the embassy has changed after the introduction of the sectoral approach in bilateral aid. What achievements have been made in education and health?

The Embassy in Sana’a (Yemen) asked the TFVG for support to conduct a gender analysis in 2008.

6. The Way Forward anno 2021

The recent IOB Report: “Gender mainstreaming in the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Beyond ‘Add women and stir’?; (2021) evaluated and summarized the current situation of MoFA/DGIS with regard to its formulation, implementation and monitoring and evaluation of its gender policies and capacity development.

It recalls that the organisational structure, that was set up to achieve the gender equality ambitions, including gender mainstreaming in the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, has not changed fundamentally since 2015. The Task Force (TFGV) at the ministry in The Hague has a pivotal role, complemented by a network of gender focal points (GFP), who are mainly junior (female) policy officers and staff in the Dutch missions abroad.

While overall this set-up has been functional, the evaluation has identified some critical issues.

In summary some critical issues are:

- The level of institutional embedding of the Task Force within the ministry has not been conducive for ministry-wide gender mainstreaming. As a result, gender mainstreaming has remained a theme that is primarily relevant for Dutch development cooperation.

- There has been little change in the staffing of the TFGV while its project portfolio has more than doubled in value since it was established. Staffing for gender mainstreaming has remained an issue for many years and requires the TFGV to perform a balancing act when combining its programme management, gender diplomacy and gender mainstreaming tasks.

- In ministry departments and the Dutch missions, the position of gender focal points remains voluntary and informal to a large extent. The challenges they face have not changed drastically since 2015: there are various interpretations of the GFP role

- Gender mainstreaming is not a standard part of staff performance appraisal.

- Interaction among the GFPs has remained limited.

- Accountability of (senior) staff for women’s rights and gender equality has remained an issue to be resolved as well.

The number of gender experts, both within the Ministry and at Embassy level has decreased and up till now the existing thematic experts have a feeling that they are “the last of the Mohicans” and often they are being asked to perform additional tasks.

And although a lot of progress, experiences and knowledge has been gained through the years with regard to women’s development and gender equality, progress seem to be halted. For many years Dutch aid often has been an example for other donor agencies, and highly appreciated by the international women’s movement. This pioneering role, for some time now, has been abandoned. Partly as an effect of cost-cutting measures of development budgets, a general trend to minimize development expertise, more focus on “Aid and Trade”, crisis- and conflict interventions and a preference for funding large scale “Partnership Programmes” through tendering procedures. Gender focal points indicated that a better understanding is needed of how the gender analysis influences the subsequent stages of the policy cycle, including evaluation design.

MoFA’s policy on Gender continues with dual pillars:

(i) Women’s Empowerment and (ii) Gender Mainstreaming, as defined as “…the process of systematically recognizing and taking into account gender issues (such as differences between the conditions, roles and needs of women and men) within core activities of projects and programmes that are initiated to address a thematic areas of international development (such as food security, education, health, water)”.

And the Ministry is clear with regard to Women’s Rights:

"Women’s rights are human rights, and equal opportunities for women and girls in political, economic and societal processes are seen as a condition for sustainable development. To accomplish gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls, efforts in all aspects of policy are needed."

In combination with years of experience and lessons learnt MoFA/DGIS will have new opportunities to strengthen the capacity to implement its policies regarding gender. As long as these “lessons learnt”, combined with adequate funding and political will, taking into account the recommendations of the recent IOB report there is hope for the future!

The IOB Report ends it recommendations on gender with following quote:

"In conclusion, true gender mainstreaming goes beyond the ‘add women and stir’ approach where women are invited to participate in interventions, the design of which has not changed. If gender mainstreaming aims to be transformative, a more comprehensive approach is needed. Such an approach would include the integration of gender equality targets throughout all phases of the policy cycle and take male perspectives on board. Expectations for transformative change in short-term and small-scale projects should however always be treated realistically and only be addressed in projects and evaluations that are able to reflect on such high-order processes, such as country-level evaluations that review a period of 10 to 15 years."

Notes:

[1] Most information of these paragraphs are based on written comments of Claudine Helleman.

[2] The terminology changed from sector specialist to thematic expert and senior policy advisor.