Rise of the Republic

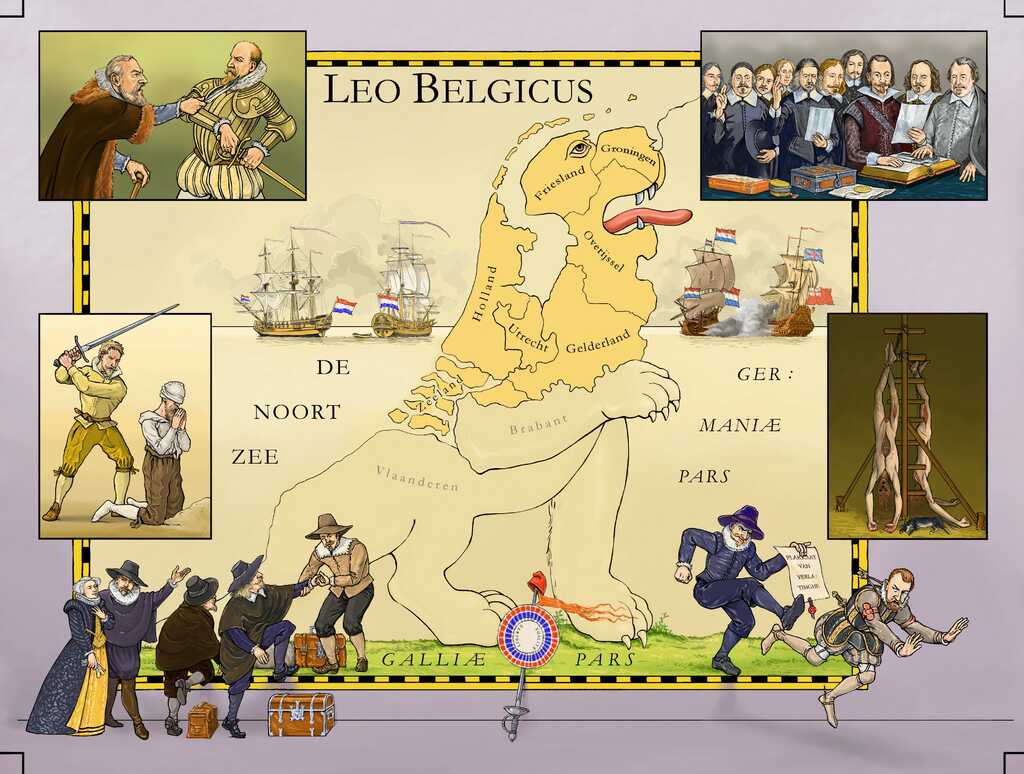

Once the Northern Netherlands cease to acknowledge King Philip II as their sovereign, their attempts to find a new sovereign fail. In 1588, the States General, representing the rebellious territories, decide to adopt sovereignty themselves and form the government of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. Several other republics exist, such as Venice and Genoa, but in an era during which monarchs increasingly tend to seek absolute power, this remains an unusual constitution.

Chief official of Holland

Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, born in the Dutch city of Amersfoort, rapidly gets ahead in the district of Holland. He is the confidante of stadtholder William of Orange. In 1586, he is appointed Grand Pensionary (also referred to as Land’s Advocate) of the States of Holland, which makes him their chief official. He turns the Republic into a well-functioning entity.

Holland is wealthy and, as the district that brings in the most money, it also holds the largest vote in the Republic. Van Oldenbarnevelt ensures that he becomes the key figure in the States General. His leadership enables the States General effectively to levy taxes and carry out a successful offensive against Spain. He pursues political compromises and if he fails, he tackles his opponents with bribery, threats, and military power. Furthermore, he initiates the establishment of a trade organisation, the Dutch East India Company. Van Oldenbarnevelt operates as a type of Prime Minister, Finance Minister, and Foreign Affairs Minister all at the same time. He is well respected at home and abroad and is regarded as the driving force of the Republic.

Conflict and beheading

Eventually, Van Oldenbarnevelt is faced with a rival: stadtholder Prince Maurice, the son of William of Orange. A stadtholder (literal meaning: deputy) is appointed by the monarch to govern on his behalf, but as a republic does not have a monarch, this original task is now defunct. Formally, the stadtholder is no more than a servant to the States General. However, as a leading aristocrat and supreme commander of the armed forces, Maurice towers far above all the other administrators.

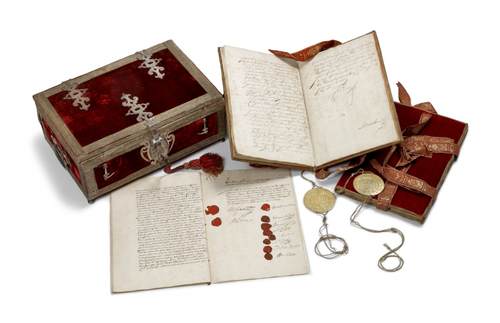

For a long time, the Republic flourishes under their joint rule. Van Oldenbarnevelt focuses on politics, whilst Maurice limits himself to his military role tasks – a perfect collaboration, or so it seems. However, after 1600, they regularly clash. Maurice wants to continue to wage war against Spain, whereas Van Oldenbarnevelt signs a truce, the Twelve Years’ Truce (1609-1621).

In addition, the Grand Pensionary wants to prevent religious quarrels within the Protestant church. He appears willing to call in army troops to enforce his intentions. Thus, he encroaches upon the stadtholder’s domain. Maurice feels threatened and removes Van Oldenbarnevelt’s authority. Eventually, he has him arrested. To his own astonishment, the Grand Pensionary is sentenced to death on a charge of high treason. On 13 May 1619, Van Oldenbarnevelt is beheaded on a scaffold in front of the Knights’ Hall in The Hague. This drama is exacerbated by the fact that his conviction is initiated by the son of his hero, William of Orange.

Johan van Oldenbarnevelt has been instrumental in the expansion of the Republic to one of the main powers within Europe. However, the power struggle between the Grand Pensionaries and the stadtholders of the House of Orange still continues for quite some time.